Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

A container declared as full of Ecuadorian banana exports hid blocks of drugs in the refrigeration panels.

After this discovery, on May 8, 2023, the Police reported that the container held more than 44 kilos of cocaine destined for Bulgaria.

Barely a fortnight later, the Police stopped another shipment carrying more than two tons of cocaine destined for Germany camouflaged in boxes of the same fruit in the port of Guayaquil. Between the two seizures, the Italian Financial Police seized 2,734 kilos of cocaine stuffed in boxes of bananas that had left Guayaquil for Armenia. The cargo was intercepted during a stopover at the port of Gioia Tauro in Calabria, in southern Italy.

Drug traffickers desire the iconic Ecuadorian fruit for its exportation volume and routes. A weak and outdated system, an insufficient review of the charges, and impunity surrounding most drug seizures show the inability of the State to face this new plague.

The authorities in Ecuador do not investigate the legal representatives of companies registered as exporters of these contaminated shipments. Several cases reflect impunity in the Ecuadorian judicial system against people who have used the export of bananas as a facade for drug trafficking without major obstacles on the part of the State.

Such is the case of the Albanian citizen Arber Cekaj, owner of Arbri Garden, a company registered in 2012.

Three years after the registration, the Police arrested a driver carrying one of the containers with his cargo to the port of Guayaquil for trafficking illegal substances in Milagro, one hour from his destination.

According to the file, inside the container were eight bricks of cocaine that weighed 28 kilos. The driver claimed that he was not driving the truck, that it was parked, and that his only job was to transport the cargo of bananas to the ports. He was then found innocent and released.

Cekaj, on the other hand, was linked to the trial 23 days after the driver’s arrest since the prosecution connected him with handling the cargo when he bought the fruit at a ranch in Milagro. His capture was requested, but Cekaj never appeared personally and evaded Ecuadorian justice.

Arbri Garden continued to export bananas for three more years until Cekaj was arrested in 2015 in Albania for another contaminated shipment that left Colombia. The case opened for drug trafficking in Ecuador is not solved, and the company no longer appears in the exporters register.

An investigation by TC Television and CONNECTAS reveals that the vulnerabilities of the Unibanan system—which should regulate the export of fruit—and of the protocols of the Ministry of Agriculture, the Counter-Narcotics Police, and justice operators promote the export of drugs from Ecuador in banana shipments.

Anti-narcotics reveals that of the 326 drug seizures in banana cargo in the last five years, 127 companies were detected as responsible, and 60 of those are repeat offenders in finding the alkaloid in fruit shipments.

Cross data from the Ministry of Agriculture, which authorizes and regulates the export of bananas, and the Anti-Narcotics Police show that more than a dozen companies maintain these quotas even though drugs have been found in their goods.

The lack of articulated follow-up of institutions for drug confiscation cases in bananas motivates a chain of corruption that goes from State agencies to carriers and reaches the ports, according to Special Narcotics Prosecutor César Peña.

In 2022, former undersecretary of Musáceas and now Deputy Minister Paul Núñez reported to the Prosecutor’s Office the manipulation of the Unibanan system: for eight years, a fictitious plot recorded the export of more than one million boxes of bananas every week. Within the Ministry, the chain of officials responsible for the management of the Unibanan system was dismissed. Still, most of the officials were later reinstated.

This happened without knowing how the system was manipulated and who was responsible. The denunciation of influence trafficking that involves the Unibanan system has not registered advances in the Ecuadorian justice portal.

Although the authorities are already aware of these vulnerabilities, the inaction of several state agencies in the banana export chain leaves the door open for drug trafficking. It also tarnishes the reputation of Ecuador’s flagship fruit.

Ecuador gained prestige in the 50s as the world’s first banana exporter. Since then, this fruit has been the first non-oil export product of the country, although, in 2022, the shrimp displaced it.

But this fruit is increasingly viewed with more suspicion in international ports. Of the 77 tons of alkaloids seized in all Ecuadorian ports in 2022, 61% are shipments of bananas. Last year, there was an increase of 233% in drug seizures in the fruit load, even when exports declined by 12%.

Drug trafficking has been a real scourge for banana producers and exporters. José Antonio Hidalgo, executive director of the Banana Exporters Association of Ecuador, reports that the private sector has invested more than 100 million dollars in improving security. Still, the public sector also needs to do its part.

“It is a great challenge. Being the product with more volume in the country, with 66% of the 7,000 containers weekly, with routes that go by 40% to the United States and Europe, the risk increases,” says Hidalgo. , says Hidalgo.

Banana producers and exporters agree that it is vital to update the software of the banana control system, which currently allows irregularities in the use of export quotas and false shipments that harm producers and encourage drug trafficking and tax fraud.

In 2022, the then Minister of Agriculture, Bernardo Manzano, promised to have the update of the Unibanan system ready by March 2023. But the official resigned after being questioned about his connections with Ruben Cherres, a businessman linked to Albanian mobsters and murdered in Santa Elena in 2023. Since then, Eduardo Izaguirre has assumed this portfolio of State.

So far, the promised update has yet to materialize. In light of internal Ministry documents, it is estimated that it would arrive only in November 2024. Until then, and in the words of the minister, the scarce controls of the production chain of the fruit icon of Ecuador are made with a “pencil, eraser and a calculator.”

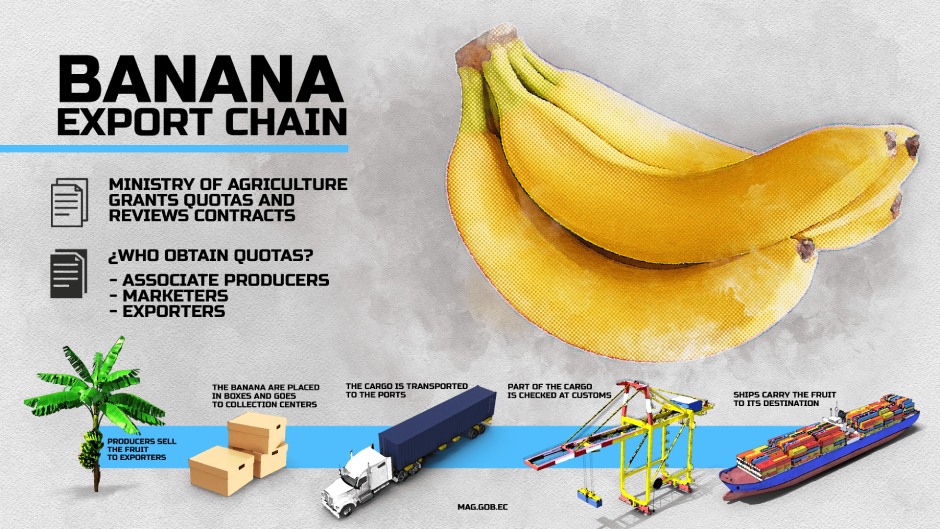

In Ecuador, there are 279 companies authorized to ship an average of eight million boxes of bananas each week. The number includes associations of producers who have land, exporters who buy the fruit from them, and marketers.

In 2012, Ecuador implemented a system of export quotas to control that the supply of fruit does not affect the price at which it is sold in the international market and maintains competitiveness.

For more than ten years, the banana control system has given them a quota commensurate with the number of hectares sown, regulates the annual price of the banana box, regularizes contracts between producers and exporters, and carries out the country’s banana cadastre.

To send the fruit abroad it is required to be registered as an exporter or as an association of producers with registered and productive hectares, and, in theory, a verification is made in the territory that land is used for the production of bananas.

As for the marketing companies, they must sign contracts of sale with the producers and then present to the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Bank guarantees that they can support these contracts. The export quota will depend on bank guarantees and the number of boxes contracted. The problem is that exporters and shell companies, which have no land or banana production, sneak into the system but quotas to send the fruit.

In 2022, an audit by the German Technical Cooperation (GIZ) detected weaknesses in the security of the Unibanan system. In October of that year, an official of the Ministry of Agriculture filed a complaint with the Attorney General’s Office for alleged trading in influence. The complaint explains that the Ministry allocated a quota to export bananas to a property of 20,000 hectares, the equivalent of 20,000 soccer fields, that does not exist anywhere in the country. That phantom exporter recorded shipments of one million 200,000 dummy boxes every week.

The rarest thing is that the property authorized between 2014 and 2022 as an exporter of bananas was in the name of the Ministry of Agriculture, although neither this nor the State, in general, produce or export the fruit directly. The rarest thing is that the property authorized between 2014 and 2022 as an exporter of bananas was in the name of the Ministry of Agriculture, although neither this nor the State, in general, produces or exports the fruit directly.

“The control—of the recorded data—is non-existent because there is not enough staff for this, why they did not continue to audit,” says a senior official of the Ministry of Agriculture who asked to reserve his name.

Under this system, which depends on the Under-Secretary of Musáceas of the Ministry of Agriculture, less than 30 persons work who the minister appoints, and their positions are of free removal.

Paul Núñez Antón, current Deputy Minister of Productive Development, confirmed that the failures allow all kinds of irregularities: some companies lend the quota to others, that there are false shipments and exports out of contract. “We have 279 cadastral companies among marketers, associations of producers, and exporters. Then, as the audits go out, we realize what there is. We found codes that do not exist, farms that do not exist...” he said.

Despite the State’s knowledge of these gaps, the rebuke of influence peddling involving the Unibanan system does not record any progress in Ecuadorian justice. One of the two officials mentioned works in the Ministry and has been there since 2021.

Minister Eduardo Izaguirre said that the manipulation of the system was internal and that 17 officials of that unit were dismissed. Still, Deputy Minister Paul Núñez clarified for this investigation that ten of those 17 people were reintegrated.

There are information gaps and obvious inconsistencies in the official list of 279 companies authorized to export bananas. There is a company that has the establishment closed, according to the Internal Revenue Service, and several companies that report the same address. In addition, the Ministry of Agriculture said that 40 producers still need an address registered in the banana control system.

The updating of the banana control system is a repeated request from exporters and producers. “It is clear that in writing, and several times, we have followed this issue in each of these transitions of four ministers that have been in Agriculture in two years,” says José Antonio Hidalgo, leader of banana exporters. This would allow, for example, the code to identify companies authorized to export is the Single Registry of Taxpayers to the Ecuadorian Treasury (RUC), which is intertwined with the system of the Internal Revenue Service and Customs to avoid tax fraud.

But this articulation is not happening, and a sector of banana producers considers that this responds to a “quota traffic” that could favor those who have the money to pay for a place to export.

Presley Andrade, a banana producer of Mariscal Sucre in Guayas, reports that individuals “ask between 400 and 600 dollars per hectare. We don’t need the minister to change, just the political will to change the software. Millions of dollars go into your pocket because here are the men in the briefcase”.

Most companies with banana export quotas were created between 2013 and 2023: 169 companies. The current time of the banana control system coincides with an increase in the creation of companies with export quotas.

Special Narcotics Prosecutor César Peña also points out that in his investigations, he has established that mafiosi buy export quotas to exporters, producers, and authorized marketers.

“For example, I am a producer, and the narcos tell me that they pay twice the price to use your export quota and your fruit, but they are not interested in bananas but in the quota.”

According to officials of the Ministry of Agriculture, this sale of quotas is not illegal. Suppose an exporter is going to send 100,000 boxes and cancel the order. In that case, another exporter can do business and send those 100,000 boxes with their brand. “Yes, that’s called selling. And it could also be used to distort”. The minister Eduardo Izaguirre explains that they found that quota sales occurred in 50% of cases and that they have reduced it to 10% “because we can not take away the possibility of helping each other.”

The vulnerabilities of the system and its effects have been reported to the Ecuadorian Government. Segundo Solano, vice president of the National Federation of Banana Producers of Ecuador (Fenabe), says that they informed the Government of President Lasso in 2022. “The software has not been changed and is being hired since the Prime Minister arrived, and there are four ministers. That it is in tender, that already comes, but there is the interest to change and make this business transparent, and the State is injured in this”.

The Minister of Agriculture acknowledged the flaws in an interview for this research and warned about the challenges: “The number of variables that exist within the system is enormous, and who has to build it has to guarantee that there will be no capacity to violate the system.” Therefore, it will not be possible to have a faithful banana control system until at least 2024. “Here, what counts is the intention. If we have to do it with a calculator, pencil, and eraser, we are doing our best with the tools we have while we bring the tool that will cut this”.

The problem goes beyond a technical issue of the system. It goes through the lack of control over companies reported for drug seizures, which may continue to export.

The Ministry of Agriculture of Ecuador does not register companies whose containers drugs have been seized and therefore does not sanction them.

Nickola Mora, undersecretary of Musáceas, stated that these issues are handled exclusively by the Narcotics Police. The Ministry of Agriculture, he explains, could temporarily take away his quota and penalize a company that does not fulfill the contract, does not pay the official price of the box (6,50 dollars), or falsifies the shipping plans.

In contrast, the director of Narcotics, Pablo Ramírez, says that after each seizure, “the information has been transmitted to the respective ministries so that the corresponding procedures are followed.”

But the Ecuadorian Ministry that grants the export quotas does not have that record, nor does it have a system articulated with the Internal Revenue Service that allows us to know if there are inconsistencies in physical addresses or anomalies in the taxes.

Anti-narcotics reveals that of the 326 drug seizures in banana cargo in the last five years, they found 127 companies responsible, and 60 of those are repeat offenders. According to a police source, 12 of these companies maintain their quotas even though narcotics have been intercepted in their cargo on more than one occasion.

Kléber Sigüenza, president of the Chamber of Agriculture, heads a family group that has more than 500 hectares of fruit production in four cantons of Ecuador. Admits that his cargo had drug contamination on one occasion but did not know what the investigation was and that it is well known that “the containers are contaminated through these quotas,” but considers that this is not the responsibility of producers or exporters but of criminal networks.

In addition, he notes: “This worries us because the image of the country is at stake, the image of the business itself, and we have a long-term business.”

Only in April of this year, Narcotics proposed a protocol that seeks to “reach a certification of exporting companies and all actors in the logistics chain, to obtain a certification that gives guarantees of an export free of drug contamination.” This would reduce the number of repeat companies sending alkaloids to Ecuadorian bananas.

But this protocol is not a regulation, and neither is it a law. It is a commitment that could reach owners of shipping companies and container yards, producers or exporters, and carriers to cooperate with the Police and obtain the certificate.

Currently, there are no companies sanctioned for transporting narcotics in their products. Still, the Ministry of Agriculture did open administrative files against two companies, in May 2023, for more than 100 false shipments that allowed the export of bananas. In a press release, that office announced that these two companies could face fines of more than 80,000 dollars and temporarily suspend the quota for 15 days. “These [cases] are going to be followed up because we also have to give them the right to defend themselves,” concludes the undersecretary of Musáceas, Nickola Mora.

Until May this year, of the 78 tons of drugs the Police had seized, most (43 tons) were found on roads and collection centers. That is, before the cargo reaches the ports, according to the director of Narcotics.

For this reason, the export sector has proposed to the public forces and the competent institutions the implementation of protocols of control of the farm to ports. It has also identified the routes with more incidents and different levels of risk, information that has been exposed at security tables before the Government, according to the statement of the leader of banana exporters.

But, despite any isolated effort and all the requests from the private sector, the difficulties of banishing the narco from the origins of a banana load persist. For the Ecuadorian Police, it is clear that the ports are beginning to be the point at which “all containers that are already contaminated in one way or another are gathered,” says the director of that office, Pablo Ramírez.

“Since the end of last year, we have carried out a security protocol for the banana export chain. We have information through customs documents that help us to profile certain risk indicators that make us presume that some contamination would exist in the container,” Ramírez explains.

But not all containers arriving at the port are checked. The percentage of containers inspected is between 38 and 40 percent.

At the beginning of the year, the Government promised to install twelve scanners that would check all the cargo more quickly. At the end of this report, only one works in the port of Posorja, in Guayaquil, and the authorities have proposed a new date for the installation of the others, by September 2023.

Until then, authorities perform random and manual inspections. In cases where there are drugs, the company’s legal representative that owns the container or the person responsible is apprehended and taken to a hearing so that justice follows the corresponding administrative procedures.

But the process can make water if the legal representative proves that he did not know the cargo and that his container was contaminated, explains Antonio Gagliardo, former Prosecutor of Guayas. “I can be a banana exporter and hire a company that rents containers to make a banana shipment to Romania; that same company delegates someone to be responsible for that cargo. Many people are involved, for example, the one who puts the cargo in the container, a customs agent. The prosecution must determine who is the determining factor, which is not always the one in the last act. It is an issue that must be more analyzed; it cannot be charged in this way,” agrees a lawyer who sponsored an arrest for drug trafficking in Ecuador.

The specialized Prosecutor César Peña adds another element: “The modus operandi of Russians or Albanians is that they put anyone as legal representative -of the exporters- they are using older adults, people without a record and, if there is a confiscation, there are no elements of linkage.”

The director of the Anti-Narcotics Police corroborates this when he reports for this investigation that they have identified that “foreigners who come with money and under the facade of investors, buy exporters with a certain historical level of export quite considerable” and choose bananas by volume and routes.

Proof of this is what happened in 2013, when Adriatik Tresa, Nikolaos Gianokopolous, and Petrov Ivanov were arrested in a raid for the investigation of money laundering, with more than 120 thousand dollars in cash in a residence of the exclusive sector of Samborondón, a few minutes from Guayaquil.

Tresa allegedly arrived in Ecuador a few days before his arrest. The process stated that the three declared they would use that money to buy bananas, qualify as fruit exporters, and send “20,000 boxes per week, for which they had to guarantee 126,000 dollars to be delivered to the Ministry of Agriculture”. All three were released, but Tresa failed to become a buoyant banana exporter. He was killed in his home with six rifle shots in 2020.

According to the Prosecutor, the cracks in the controls for the export of bananas, which allow the existence of ghost farms and the sale of quotas, are armed casually for that. “From hand to hand, an elephant is lost,” he says metaphorically.

“The legal representative will say that he does not know and that all his documents are in order, the locks were never opened, and the driver asked. The driver will say he never stopped on the road. The company who sold the banana will say that they have minutes of having delivered everything in order”, illustrates Peña.

Prosecutors and Police specialized in Narcotics know that drug-trafficking organizations use leads to register them as responsible for the shipments or legal representatives of the companies since their appointment lasts five years.

Tracing the family and business links of each of the shareholders and legal representatives of the companies whose cargo narcotics were found is “an octopus task because you have to follow all the tentacles,” says researcher Peña. And although he admits that the Prosecutor could do it ex officio, he says “it is delayed.”

The preliminary investigation may last six months and two years to gather evidence and evidence with the support of the Police.

Anti-narcotics argues that the names of companies authorized to export bananas indicated by recurring drug shipments could be made public only after a judgment.

Delay limits the exercise of justice. The Ecuadorian Observatory of Organized Crime collects data from the Ecuadorian Prosecutor’s Office. It reports that only 15% of drug trafficking cases reached a sentence between 2019 and 2022.

Thus, while the officials are blaming themselves, the inaction of the State in the face of the plague that affects the Ecuadorian banana leaves the door open for drug traffickers to appropriate the country’s flagship product.